What is Personality?

‘The sum total of an

individuals characteristics which make him or her unique’

(Gill, 2000)

Whilst it is difficult to truly identify what personality is (Cashmore, 2008) the general consensus is that it's a combination of hereditary traits which make us unique. It is these characteristics which determine

how a person will react in any given situation, which in this case is a

sporting environment.

Trait theorists believe that personality is determined by

inherited characteristics, and therefore that our behaviour is genetically

programmed (Weinberg & Gould, 2011). For example, a person may

naturally display calm, thoughtful and reliable characteristics which would

consistently reflect in their behaviour, and determine their behaviour in all

situations.

This is depicted as:

B=F(P) (Behaviour is a function of

personality)

(Pearson Schools, 2008)

In 1990 Girdano presented the Narrow Band Approach – a trait

theory. Girdano believed that

individuals can be split into two groups based upon their personality: Type A

and Type B.

Type

A

|

Type

B

|

Competitive

|

Non-Competitive

|

Likes Control

|

Does not Enjoy Control

|

Strong Desire to Succeed

|

Un-ambitious

|

Suffers Stress

|

Relaxes Easily

|

Works Fast

|

Works Slower

|

(Pearson Schools, 2008; Gill, 2014)

One of the strengths of this theory is that whilst looking

at the characteristics above, we all know people that we are able to say have

either Type A or Type B personality, so it does work in reality. However, the approach is too simplistic and

athletes do not simply fall into one category or the other, they may lie

anywhere in the middle of the spectrum.

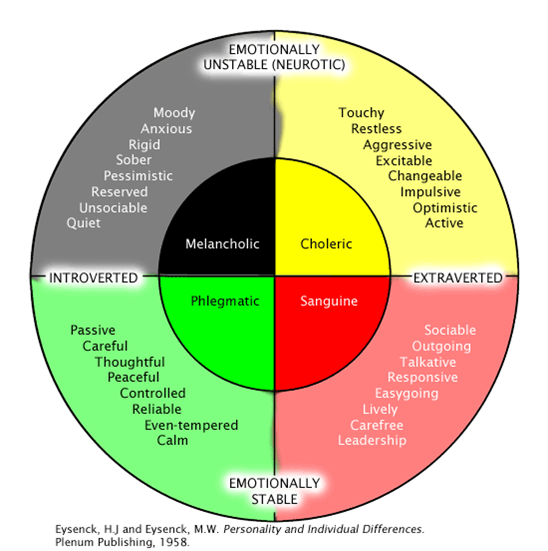

Another trait approach was presented by Eyesenck, who

produced an Inventory which measures personality across two dimensions:

Introvert – Extrovert, and Stable – Neurotic, therefore a personality can be

placed into one of four quadrants shown on the diagram below (Gill, 2014; Weinberg & Gould, 2011).

Once again, when looking at certain athletes (or sports) we

are to place them in one of the four quadrants above. For example, we would usually say that a golfer is introverted/emotionally stable as they are generally controlled, careful and thoughtful. Another strength of the theory is that it’s

not as simplistic as Girdano’s theory, as it considers more than one dimension. It is, however, still a relatively basic

approach and works on the assumption that an individual’s behaviour will not be

influenced by the environment, which we know from personal experience is not

always the case (Pearson Schools, 2008).

Freud believed that our behaviour is a combined result of

constantly changing restraints, rather than specific personality traits, and

this is modelled in his Psychodynamic Approach.

It places emphasis on what Freud calls our instinctive drive (ID), which

are our basic instincts over which we have no conscious control, and how they

conflict with the more conscious parts of our personality (Weinberg & Gould, 2011). Our Ego is the conscious link between our ID,

and how we react to fulfil that desire, but it may be inhibited by our

Superego, which is our moral conscience which will tell us what that behaviour

is appropriate. It is an interaction of

these dynamic processes which produces our behaviour in a sporting environment (Gadsdon, 2001; Cashmore, 2008).

Weinberg & Gould (2011) state that although this method is not widely used, predominantly

because of the difficulty in testing and measuring the aspects involved, it

highlights that not all aspects of behaviour are under conscious control. However, another weakness of Freud’s approach

is that it focuses on behaviour being a result of internal factors, and doesn’t

consider how the environment affects our behaviour.

Bandura Social Learning Theory

The state approach to personality argues that our behaviour

is a product of the environment which is based upon Bandura’s Social Learning Theory (1963).

Bandura stated that we learn our behaviour through observation (modelling) and feedback (social reinforcement), and therefore that it is the environment that determines our behaviour (Weinberg & Gould, 2011).

B=P(E) (Behaviour is a product of the environment)

(Pearson Schools, 2008)

Bandura stated that we learn our behaviour through observation (modelling) and feedback (social reinforcement), and therefore that it is the environment that determines our behaviour (Weinberg & Gould, 2011).

In contrast to the trait theories displayed above, the

social learning theory puts the emphasis solely on the environment. Although

environmental restraints may change an athlete’s behaviour, this is not always

the case as personal beliefs and characteristics sometimes overrule the

requirements of the situation. For

example, when watching throwing in track and field you often hear coaches

telling their athletes that they need to be ‘more aggressive’, but it isn’t a

disposition which people are able to turn on and off dependent on the

environment.

Hollander's Theory of Personality (1976)

Hollander's Theory of Personality (1976)

Hollander produced a model which splits personality into

three layers: psychological core, typical responses, and role related

behaviour . The psychological core is

thought to be the ‘real you’ – the most enduring aspect of your personality,

typical responses is based upon the social environment and previous experiences

which you’ve learnt and stored, and finally role related behaviour which is the

aspect of your personality most susceptible to change dependent upon the

environment (Pearson Schools, 2004; Weinberg & Gould, 2011; Gill, 2014). For example, a footballer might typically be a calm and controlled person (psychological core) but during a game of football he may become aggressive especially when trying to gain possession of the ball due to the nature of the game (role related behaviour).

(Image taken from Gill, 2014)

Personality is an influential factor in all of the concepts

that will be discussed in this blog, and it can be used by psychologists to predict an athlete’s

behaviour and therefore prepare them for a specific situation.

References:

Gill, A. (2014) Personality and Sport [PPT] FdSc Sport Coaching, Chesterfield College, February 2014.

Gill, D. (2000) Psychological dynamics of Sport and Exercise. Human Kinetics: Illinois.

Pearson Schools (2008) Chapter 8: Sport Psychology [online] Available from: http://www.pearsonschoolsandfecolleges.co.uk/Secondary/PhysicalEducationAndSport/16plus/OCRALevelPE2008/Samples/A2PEStudentBookSamplePages/PEforOCR(A2)SBCH08.pdf [Accessed 12th March 2014]

Weinberg, R. & Gould, D. (2011) Foundations of Sport and Exercise Psychology (5th Edition). Human Kinetics: Leeds.

Cashmore, E. (2008) Sport and Exercise Psychology: The Key Concepts (2nd Ed.) Routledge: London.

Gadsdon, S. (2001) Psychology and Sport. Heinemann: Oxford.

Gill, D. (2000) Psychological dynamics of Sport and Exercise. Human Kinetics: Illinois.

Pearson Schools (2008) Chapter 8: Sport Psychology [online] Available from: http://www.pearsonschoolsandfecolleges.co.uk/Secondary/PhysicalEducationAndSport/16plus/OCRALevelPE2008/Samples/A2PEStudentBookSamplePages/PEforOCR(A2)SBCH08.pdf [Accessed 12th March 2014]

Weinberg, R. & Gould, D. (2011) Foundations of Sport and Exercise Psychology (5th Edition). Human Kinetics: Leeds.